Five Burning Questions about the Indonesian Personal Data Protection Bill

After more than two years in the pipeline, the Indonesian Parliament finally passed the long-awaited personal data protection bill (“PDP Bill”) on 20 September 2022. Once the PDP Bill is enacted into law, it will be the basis for personal data protection matters in Indonesia, and this means that existing laws that contain personal data protection rules must be brought in line with the provisions of the proposed personal data protection law (“PDP Law”).

The PDP Law sets out normative provisions for personal data protection, as opposed to detailed or practical rules. Thus, the government will have to issue implementing regulations in the future to further regulate the provisions in the PDP Law.

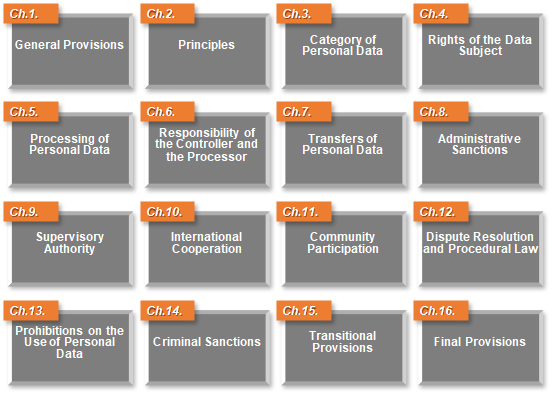

The PDP Law consists of 76 articles that are grouped into 16 chapters:

Given the extensive content of the PDP Law, we will be issuing a series of alerts on this topic. But for now, we will answer some of the burning questions surrounding the PDP Law that we have received so far.

Once the Parliament passes the PDP Bill, does it mean that Indonesia finally has a comprehensive personal data protection law?

For now, the answer to this question is no as the PDP Bill has not been enacted into law. While several publications may have suggested that the PDP Bill had been passed into law following Parliament’s approval at the plenary meeting on 20 September 2022, we wish to make it clear that that this is not the case.

Based on the legislative process in Indonesia, the President must sign and enact the PDP Bill for it to become a law. Assuming the approved PDP Bill was presented to the President on the same day as it was approved by the parliament, then from 20 September 2022, the President has 30 calendar days to do so, failing which the PDP Bill will automatically become a law.

What is considered “personal data” under the PDP Law?

Personal data is defined as any data relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (in this case, “data subject’) that can be identified on its own or in combination with other information either directly or indirectly through an electronic or non-electronic system. Based on this definition, the PDP Law does not exempt the manual processing of personal data like its GDPR inspiration.[1]

The PDP Law categorises personal data into two, namely (a) general personal data and (b) sensitive personal data. The PDP Law offers a non-exhaustive list of examples for each category:

General personal data

This category consists of an individual’s:

- full name;

- gender;

- nationality;

- religion;

- marital status; and/or

- a combination of personal data that identifies a person (e.g., cell phone numbers and IP addresses).

Specific personal data

This category consists of:

- data concerning health;

- biometric data;

- genetic data;

- criminal record;

- child’s data;

- personal finance data; and/or

- any other data deemed as sensitive personal data under the law.

Who is affected by the PDP Law?

Material scope

The PDP Law applies to personal data processing by private or public parties, although there are exemptions to the PDP Law’s application. Full exemptions of the PDP Law apply in the case of personal data processing for personal or household activities. Unfortunately, the PDP Law is silent on what those activities are. We expect this will be elaborated under the implementing regulations of the PDP Law. For reference, under the GDPR, purely personal and mere household data processing activities may include personal correspondence, keeping an address book or social network accounts, and online activities (as a private individual) with no connection to a professional, full-time, or commercial activity.

There are also partial exemptions for some provisions in the PDP Law. For example, certain data subject’s rights can be derogated when the purpose of the processing of personal data is for:

- national security and defence purposes (e.g., a police investigation);

- law enforcement measures (e.g., prosecution of criminal offenses);

- public interest purposes (e.g., citizenship administrations, social security, taxation, licensing);

- monitoring/supervision in the financial services sector, monetary, payment, or financial stabilisation (i.e., which fall under the supervision of Bank Indonesia, OJK (Indonesia’s Financial Services Authority), and LPS (Indonesia’s Deposit Insurance Agency); or

- statistical and scientific research purposes (the PDP Law does not further elaborate this exemption category).

Territorial scope

The PDP Law has a broad territorial scope. It will impact not only Indonesian-based entities, but virtually every business dealing with data subjects within Indonesia – both data controllers and data processors (e.g., cloud-based service providers). The coverage of the PDP Law also expands to any personal data processing of Indonesian nationals abroad.

Do I need consent for every personal data processing activity?

While consent from data subjects still exists as a legal basis for the processing of personal data, it is no longer the only legal basis. Under the PDP Law, Indonesia now recognises six other legal bases that can be relied on when processing personal data:

- explicit consent of the data subject;

- contractual obligation, which is when the processing of personal data is necessary for the performance of a contract that involves the data subject as a party or to fulfil the data subject’s request before entering into a contract;

- legal obligation, namely that the processing of personal data is necessary to comply with the law that applies to the data controller;

- the processing of personal data is necessary to protect the vital interests of the data subject; or

- public interest, namely that the processing of personal data is necessary for the performance of a task in the public interest, public service, or for exercising of statutory powers (kewenangan) vested in the data controller; and/or

- legitimate interest, namely that the processing of personal data is necessary for the legitimate interests of the data controller considering its purposes, needs, and the balance between the data controller’s interests and the data subject’s rights.

This is a major development that is in line with the standard market practice (including the GDPR). Unfortunately, the PDP Law does not offer adequate clarity regarding each lawful basis (save for consent). We expect that the implementing regulations of the PDP Law will shed some light on this matter.

What are the sanctions and fines set out under the PDP Law?

Failure to comply with the PDP Law will subject a data controller (and, in some circumstances, data processors) to the following administrative sanctions:

- written warnings and reprimands;

- temporary suspension of data processing activity;

- an order to erase or destroy personal data; and/or

- an administrative fine of up to 2% of annual revenue or sales of the controller.

The PDP Law empowers a supervisory authority, which will sit within the executive branch, to monitor and enforce the PDP Law (including imposing the above sanctions). It is unclear whether this supervisory authority will be a new executive body or an existing one. What is clear is that the PDP Law contains a sunset provision granting data controllers and data processors two years to bring their data handling practices in line with the PDP Law. This means that data controllers and data processors will not be subject to the above administrative sanctions within such period.

However, please bear in mind that even if the PDP Law grants a sunset period, there are certain provisions under the PDP Law that will immediately become effective once the PDP Bill is enacted into law, i.e. provisions on prohibited conducts related to personal data (e.g., unlawful collection, disclosure and/or use of personal data). These conducts are considered criminal offenses and are punishable by fines of up to IDR6 billion (~USD400,000) and/or by imprisonment of up to six years.[2]

Conclusion: What’s Next?

Without a doubt, when the PDP Bill is enacted into law, it will have significant effects on how users of personal data collect and handle personal data. It is essential that these data users become familiar with the requirements of the PDP Law and understand its coverage and consequences to ensure compliance once the PDP Bill has been passed into law.

For now, data users should contact their counsels to consider any necessary compliance measures, keeping in mind that there will be a limited sunset period for compliance to be achieved under the PDP Law.

[1] GDPR or the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation has been heavily referred to by the Indonesian government when drafting the PDP Bill. While the GDPR is a technology-neutral regulation, it does distinguish between automated and manual processing of personal data. The GDPR does not apply to the latter to the extent such processing of personal data is not part of a filling system (a system that involves some sort of ordering of personal data, e.g., chronological, alphabetical, or categorical orders).

[2] The existing personal data protection rules will still apply before the 2-year sunset period of the PDP Law lapses. Therefore, the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology will still be authorised to monitor and enforce personal data protection rules under the Electronic Information and Transactions Law and its implementing regulations.

Daniar Supriyadi and Michelle Abiah Leo also contributed to this alert.